Top 3 Tips To Turn Your Newsletter Into a Revenue-Generating Machine (and take back your relationship with your audience/subscribers)

Brought to you by Vubble's new RevLetter Get your data in order What data do

In the media and other industries, automation is presented as a neutral process, the straightforward consequence of technological progress. It is not.

Tessa Sproule — Co-Founder and Co-CEO, Vubble

Based on a presentation to Communitech, Data Hub in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada — December 5, 2018

Whether we build it or use it or both, a lot of us think of technology as a neutral thing — something that’s working in the background: helping us by automating the annoying stuff in our day; amplifying our brightest ideas by making them even bigger, faster and more awesome; keeping us on the right track on our drive home.

But technology is not neutral.

We can not simply engineer perfect solutions to the messy problems that come with human living. Just ask Mark Zuckerberg.

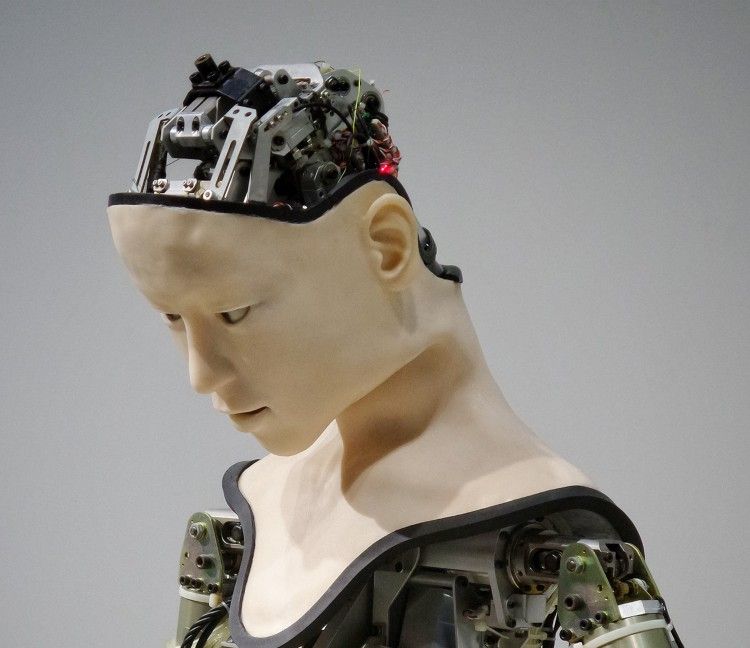

AI isn’t just one thing. It’s a constellation of things. It’s machine learning. It’s algorithms. It’s data collection. It’s data processing. It doesn’t just happen inside a computer; it happens in conjunction with real people. People who sort things. People who decide things. People who want things.

Artificial intelligence is also personal. Without our inputs, without our information, it doesn’t work. It’s not something happening by itself in a computer somewhere — it’s happening because of how you’ve interacted with it. What you’ve shared with it, knowingly or not — and what the people behind it think is important.

For me, it got very personal with information media content. In 2013, I was Director of Digital at CBC and increasingly worried about the path ahead for media as we moved quickly into a post-broadcast world.

I was worried about filter bubbles. Algorithms, largely on Facebook, were defining what most adult Canadians were watching and hearing about online. I was worried about how the public sphere would have enough shared knowledge about issues of the day to make sound policy advances. I was worried we were heading fast down a dark tunnel of clickbait, misinformation and popularity governing the information industry.

AI technology is not a tool when it comes to media. It is the master of our attention. “Attentional control” is something unique to us humans. It’s a thing that is embedded in our psychology that is very automatic — it helps you understand what is important, what you should pay attention to, what to allocate your brain powers to. In our earlier times, ‘attentional control’ was especially helpful if you encountered a bear while you were out foraging.

Today, we still possess this unique, innate trigger. Today, the media’s use of AI technology is driven by the “attention economy,” in which we buy with our likes, our views, our shares. In the “attention economy,” the most viral wins.

And the most viral tends to be the extreme stuff — the things that really anger us travel farthest and fastest. The single most popular news story of the entire 2016 US election — “Pope Francis Shocks World, Endorses Donald Trump for President” — was a lie fabricated by teenagers in Macedonia. Three times as many Americans read and shared it on their social media accounts as they did the top-performing article from the New York Times. In the final three months of the 2016 election, more fake political headlines were shared on Facebook than real ones.

When we pay more attention to something that has more likes at the expense of really important things, we’re making decisions on what’s a priority, rewriting our brains, determining whose voices are heard, whose facts dominate.

Now we carry a propaganda megaphone in our pockets, and algorithms engineered towards deeply personalized experiences that are designed to ratchet up our attention consumption — feeding us more and more of the stuff we like, the things that push our buttons, the things that grab our attention. Meanwhile, we are starving for quality information in the midst of plenty.

In the media and other industries, automation is presented as a neutral process, the straightforward consequence of technological progress. It is not.

Online, just as offline, attention and influence largely gather around those who already have plenty of both. A few giant companies remain the gatekeepers, while the worst habits of the old media model — the pressure towards quick celebrity, to be sensational above all — have proliferated in the ad-driven system.

Tech’s posture is to deny its own impact. (“We just run a platform.”) But the effects are deep, real and troubling. Just because the Internet is open doesn’t mean it’s equal; offline hierarchies carry over to the online world and are even amplified there.

A profoundly troubling area where bias is obvious and problematic is AI-driven facial recognition. For darker-skinned women, existing AI image software has a 35% error rate. For darker skinned men, it has a 12% error rate. The caucasian error rate is much lower than either of those.

And guess what happens when you add something like predictive policing to that scenario? Non-profit journalists at ProPublica audited a risk-assessment software used by American courts and the justice system to determine the likelihood that a convicted criminal will re-offend and found the system routinely and wrongly predicted black convicts would re-offend.

Work is being done to fix this, but even if biases are addressed and facial recognition systems operate in a way we all deem is fair, there’s still a problem. Facial recognition, like many AI technologies, has a rate of error even when it operates in an unbiased way. Who wants to be in the unlucky group on the wrong end of a false positive?

Here’s a secret. Big tech already knows about the limits of the technology — that humans are needed to intervene at points. What they don’t show, and we fail to see, is the labor of our fellow human beings behind the curtain.

The Moderators is a 2017 documentary directed by Adrian Chen and Ciarán Cassidy. It gives a look into the lives of workers who screen and censor digital content. Hundreds of thousands of people work in this field, staring at be-headings, rape and animal torture, and other terrible images in order to filter what appears in our social media feeds.

More people work in the shadow mines of content moderation than are officially employed by Facebook or Google. These are the people who keep our Disneyland version of the web spic and span.

Yes, AI can be used in positive and profound ways. It can be used to track a heartbeat and predict health issues and even mental health episodes before they happen. It can be used to identify a missing child. It can alert the police about a terrorist wandering in a crowd. It can help the blind understand what is happening around them in real time. It can predict — with better accuracy than human doctors — the likelihood of skin cancer based on an image of a mole.

But it can also be used in deeply damaging ways. Damaging to freedoms, human rights and our understanding of ourselves. It can be used to track you without your permission or knowledge. It might sell your interests to marketers about the shoes you looked at in the store window; it could predict that you’re probably going to get cancer to your potential life insurance provider; it could tell your boss you’re buying too much beer; it could tell the police you’re probably going to do something bad. Look to what’s happening in China right now with the euphemistically named “Social Credit System” for a stark and sobering example in action.

It all raises a critical question: what role do we want this type of technology to play in everyday society?

If we want the Internet to truly be a people’s platform, we have to work to make it so.

We are privileged to live in an advanced democratic country; we need to call on our elected representatives on issues that require the balancing of public safety with our democratic freedoms. Artificial intelligence requires the public and private sectors alike to step up — and to act.

I’m not saying the Internet needs to be regulated — but that these big tech corporations need to be subject to governmental oversight. They are reaching farther into our private moments. They are watching us. We need to watch them.

I’m for regulating specific things, like Internet access, and stronger protections and restrictions on data gathering, retention, and use. The better we can get to be out in front of the social consequences of AI, the better for all.

Yes, it’s unusual for a company to ask for government regulation of its products, but at Vubble we believe thoughtful regulation contributes to a healthier ecosystem for consumers and producers alike. We advocate for a “technocracy” approach. The production of technology that doesn’t just feed our business, and that of our customers, but that does good and makes society a better place for us all.

Consider this: the auto industry spent decades in the 20th century resisting calls for regulation, but today we all appreciate the role regulations have played in making us safer. As Zeynep Tufekci put it:

“Facebook is only 13 years old, Twitter 11, and even Google is but 19. At this moment in the evolution of the auto industry, there were still no seat belts, airbags, emission controls, or mandatory crumple zones.”

The issue at stake is nothing less than what kind of society we want to be living in in the future — that we want our children to be living in. It is not enough to just build it. We need to think it through. What does it mean to be a leader in the responsible development and use of artificial intelligence — will you join us?

This list, which is by no means exhaustive, illustrates the breadth and importance of the issues involved. It’s a start, and we invite input.

There’s a role for you, the public, to play in all of this, in critiquing and voting with your ballots, wallets and attention in holding us all to account. Self regulation is no substitute for public judgement when it comes to decision making. So please, interrogate the AI in your lives. Speak up. Let us know how we’re doing and hold us to account.

Based on a presentation by Tessa Sproule to Communitech, Data Hub in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, December 5, 2018.

© 2022 Vubble Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Home • Who We Are • Contact Us • Privacy Policy • Cookie Policy